THE RISE OF AFRICAN AIRBORNE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS

As security threats across Africa grow more complex, a quiet transformation is underway in the continent’s air forces. Increasingly, African nations are investing in airborne early warning (AEW) systems radar-equipped aircraft that extend surveillance far beyond the reach of ground-based sensors. Once the preserve of major military powers, these platforms are now becoming central to Africa’s evolving approach to air defense, counter-terrorism, and maritime security.

AEW systems provide real-time detection and command-and-control capabilities against aircraft, missiles, ships, and ground movements. For African militaries that have long relied on static radar sites vulnerable to terrain and sabotage, airborne platforms offer flexibility, reach, and faster decision-making. Rising insurgency, persistent border disputes, and growing pressure on maritime routes have made such capabilities less a luxury than a necessity. Egypt, Nigeria, Algeria, and Morocco are among the countries leading this shift, signaling a broader move toward networked and intelligence-driven warfare.

Related Articles: AFRICAN AIR FORCES RISE TO THE FOREFRONT IN COUNTERTERRORISM OPERATIONS

The foundations of AEW use in Africa can be traced to the late Cold War period, when South Africa experimented with radar-equipped aircraft during the apartheid era. Modified Boeing 707s operated by the South African Air Force were primarily used for electronic surveillance and mission support rather than full airborne early warning and control (AEW&C). While limited by today’s standards, these efforts introduced the concept of airborne surveillance in the region. After apartheid, South Africa’s defense priorities changed, but the technological precedent influenced neighboring states facing rising instability, particularly in the Sahel and Horn of Africa.

Egypt has emerged as one of the most ambitious adopters of advanced AEW capabilities. Seeking to secure expansive airspace and strategic maritime corridors in the Mediterranean and Red Sea, Cairo has shown interest in platforms such as the U.S.-made E-2D Advanced Hawkeye. Such aircraft would significantly enhance Egypt’s ability to detect and track aerial and naval threats at long range. Integrated with its large and modern fighter fleet, AEW platforms would act as force multipliers, strengthening situational awareness in both conventional and asymmetric conflict scenarios.

Nigeria’s approach reflects a different but equally pressing security reality. Confronted by insurgency, banditry, and cross-border criminal networks, Abuja has focused on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR). The Nigerian Air Force operates ATR 42-500MP aircraft equipped with advanced sensor suites, including the Leonardo ATOS system. These platforms have proven effective in tracking armed groups and supporting precision strikes during operations such as FANSAN YANMA. Combined with new combat aircraft acquisitions, Nigeria is gradually building a layered surveillance and response architecture, though logistical constraints, training demands, and maintenance capacity remain persistent challenges.

In North Africa, Algeria and Morocco are integrating AEW-related technologies as part of broader military modernization programs. Algeria maintains one of the continent’s most capable air forces and has reportedly explored early warning radar systems with anti-stealth features, including Chinese-supplied technologies. Morocco has also enhanced airborne and border surveillance amid enduring regional tensions. In this strategic environment, AEW platforms provide an advantage in monitoring vast desert expanses and extended coastlines, reinforcing deterrence and early response capabilities.

External suppliers are accelerating this trend. Western firms such as Saab are marketing multi-domain AEW&C platforms like the GlobalEye, designed to operate across air, land, and sea environments. At the same time, China has expanded its footprint by exporting radar and surveillance systems to numerous African states, often with fewer political restrictions than Western alternatives. Unmanned options are also gaining attention. Drone-based platforms, including variants of the MQ-9B SeaGuardian, offer longer endurance and lower operating costs, appealing to countries seeking to monitor maritime zones, counter piracy, and combat illegal fishing.

Despite growing interest, significant obstacles remain. AEW systems are expensive to acquire and sustain, requiring robust infrastructure, skilled personnel, and long-term logistical support. Many African air forces remain dependent on foreign training and maintenance, raising concerns about operational autonomy. Export controls, geopolitical rivalries among suppliers, and limited regional coordination further complicate procurement and integration. In parts of the Sahel, where radar deployments are increasing, the lack of interoperable systems risks fragmentation rather than collective security gains.

Even so, the expansion of airborne early warning capabilities marks a notable shift in Africa’s defense posture. Beyond military applications, these platforms could support disaster response, border management, and environmental monitoring as climate pressures intensify.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace17

- Border Security15

- Civil Security6

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense24

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army9

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation7

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Policies1

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces2

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized6

- UNSC1

- Veterans7

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

DEFENCE MANUFACTURING CLUSTERS EMERGING IN AFRICA

Africa’s defence manufacturing sector is increasingly organized around specialized industrial clusters, reflecting...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOFebruary 3, 2026THE ALGERIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE: TACTICAL LESSONS

The Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962) remains one of the most instructive...

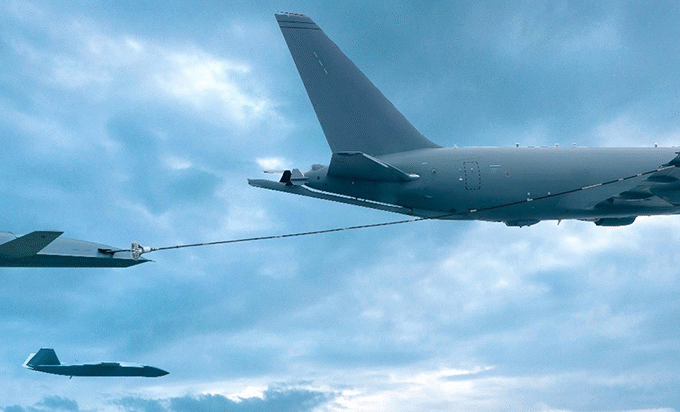

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 23, 2026AERIAL REFUELLING IN AFRICA: WHO HAS THE CAPABILITY?

Aerial refuelling transferring fuel between aircraft in mid-flight is one of modern...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 21, 2025ECOWAS MILITARY INTERVENTION IN NIGER: A TURNING POINT?

The coup d’état in Niger on July 26, 2023, marked a seismic...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 7, 2025

Leave a comment