TECHNOLOGY TRANSFER: WHAT AFRICA GAINS FROM GLOBAL DEFENCE PARTNERSHIPS

As geopolitical alliances realign, African countries are rethinking how they secure their borders and how they build their economies. Defence partnerships that once focused narrowly on arms purchases are increasingly structured around technology transfer: training, local production, maintenance capacity, and shared research. By late 2025, governments across the continent are using these arrangements to strengthen military readiness while laying foundations for industrial growth and technical skills.

For decades, Africa’s defence needs were met largely through imports, a model that was costly, slow, and strategically limiting. Equipment arrived without the expertise to sustain it, locking countries into long-term dependence. That pattern is changing. New agreements increasingly include joint ventures, local assembly lines, and workforce training. The goal is not only to field modern systems, but to build domestic capability engineering, logistics, and research that spills over into civilian industries.

Related Articles: SYSTEMS & TECHNOLOGY – THE CASE FOR SMART BORDERS IN AFRICA

China has become a central partner in this shift. Its appeal lies in competitive pricing, flexible financing, and speed of delivery, often paired with commitments to local manufacturing. Several countries have received armoured vehicles, artillery, and unmanned systems alongside training and maintenance support. In some cases, partnerships extend to establishing production facilities and research labs, particularly in drone technology. For African states under pressure to modernize quickly, this model offers access to technology without the procurement constraints often attached to Western deals.

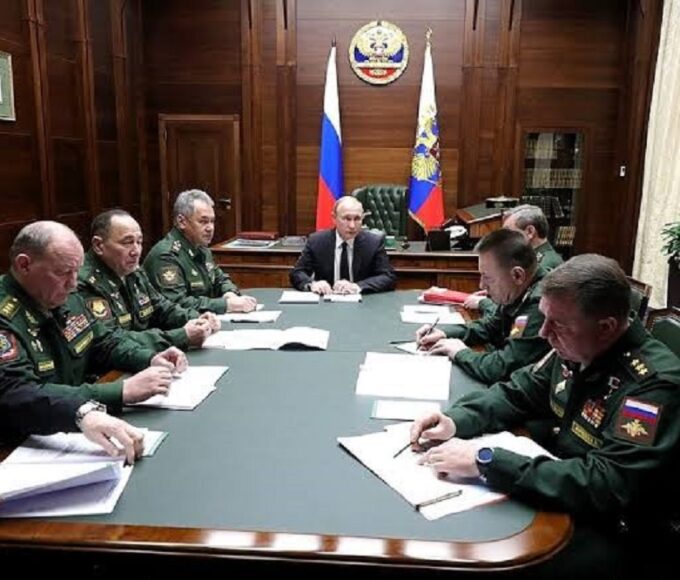

Russia is also expanding its role, particularly in C through arms exports and cooperation agreements that emphasize local maintenance and upgrades. These arrangements appeal to governments seeking alternatives amid sanctions and shifting global politics. Beyond the hardware, the value lies in skills transfer keeping systems operational, adapting them to local conditions, and gradually developing indigenous variants. Nigeria’s growing capacity to produce specialized vehicles and artillery illustrates how targeted transfers can feed broader industrial ambitions.

The United States has framed its engagement around enforceable technology-transfer mechanisms and standards. Through defence and innovation programs, Washington aims to ensure that local firms gain practical expertise in development, integration, and sustainment. Recent frameworks extend beyond traditional defence into surveillance, data systems, and emergency response technologies. For African partners, this brings access to advanced systems and regulatory know-how; for U.S. firms, it opens new markets built on longer-term collaboration rather than one-off sales.

The economic effects of these partnerships are tangible. Local production creates jobs in manufacturing, engineering, and support services. It also encourages investment in education and research, addressing long-standing gaps in science and technology funding. Defence-linked capabilities advanced materials, electronics, software, and precision manufacturing often find civilian applications, from transportation to energy. As Africa’s role in critical minerals, artificial intelligence, and clean energy supply chains grows, defence-related technology transfer can accelerate integration into high-value global markets.

Security gains are equally significant. With stronger local capacity, militaries can maintain readiness without constant external support and tailor systems to regional threats. Partnerships with countries such as India, which offers lines of credit tied to indigenous production, and showcases like the Egypt Defence Expo demonstrate how suppliers are adapting equipment particularly unmanned and surveillance systems to African operational needs. This enhances border security, maritime awareness, and counterterrorism efforts while reducing response times.

Challenges remain. Intellectual property rules can limit the depth of technology sharing, and uneven implementation risks leaving countries with assembly lines but little design capability. Over-reliance on a single partner can create new dependencies, while great-power rivalries may complicate long-term planning. To avoid these pitfalls, African governments must negotiate clear transfer terms, invest consistently in human capital, and diversify partnerships.

If managed well, defence collaborations can deliver more than weapons. They can build skills, industries, and resilience turning security needs into platforms for technological progress and sustainable development across the continent.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace17

- Border Security15

- Civil Security6

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense24

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army9

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation7

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Policies1

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces2

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized6

- UNSC1

- Veterans7

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

BEST DEFENCE POLICY PAPERS ON AFRICA IN THE LAST DECADE

Between 2016 and 2026, defence policy thinking on Africa shifted in response...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 26, 2026BEST DEFENCE POLICY PAPERS ON AFRICA IN THE LAST DECADE

Between 2016 and 2026, defence policy thinking on Africa shifted in response...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 23, 2026THE ALGERIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE: TACTICAL LESSONS

The Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962) remains one of the most instructive...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 22, 2026DEFENCE MINISTERS’ MEETINGS: OUTCOMES THAT MATTER

As geopolitical pressures intensified in 2025, defence ministers’ meetings shifted from routine...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 21, 2026