Space Situational Awareness: Protecting Africa’s Military Satellites

Military power is no longer measured solely in tanks, ships, and aircraft in the 21st century—it is increasingly defined by access to, and control over, assets in space. Across Africa, defence planners have come to recognise that satellites are indispensable for national security, enabling secure communications, intelligence gathering, navigation, and disaster response. But with greater reliance on space comes greater vulnerability, prompting African nations to explore the emerging field of Space Situational Awareness (SSA)—the ability to detect, track, and protect satellites from both natural and man-made threats.

Over the last two decades, several African states have launched satellites with military or dual-use capabilities.

- Egypt has a long track record, from the EgyptSat series to the 2023 launch of Horus-2 for high-resolution imaging.

- Nigeria’s SatX family—particularly NigeriaSat-2—provides reconnaissance data used in counterinsurgency and border monitoring.

- South Africa’s SumbandilaSat and subsequent projects have supported maritime domain awareness and environmental surveillance.

- Algeria’s AlSat constellation contributes to both civil planning and military intelligence.

While many of these satellites are marketed as “civilian,” the data they provide is critical for security operations—whether monitoring insurgent activity in the Sahel, tracking piracy off the Gulf of Guinea, or mapping disaster zones for humanitarian response.

Africa’s military satellites face the same hazards as those of any spacefaring nation, but with the added complication of limited indigenous protection capabilities.

- Space Debris: The low-Earth orbit (LEO) environment is increasingly congested. Collisions with fragments—even a few centimetres in size—can disable a satellite.

- Hostile Interference: Jamming, spoofing, or even direct-ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) weapons pose risks, particularly in regions of geopolitical competition.

- Cyber Threats: Ground stations are vulnerable to hacking attempts aimed at disrupting data flows or hijacking satellite control.

- Solar Activity: Space weather events, such as solar flares, can damage electronics and disrupt communications.

Without SSA capabilities, African nations are essentially “flying blind” in orbit, unable to detect threats in time to take protective measures.

Building SSA Capacity in Africa

SSA begins with the ability to monitor the position and condition of objects in orbit. Traditionally, this has been the domain of space powers like the United States, Russia, and the European Union, whose ground-based radar and optical tracking systems maintain vast space object catalogues.

African SSA capacity is still nascent but growing:

- South Africa operates the Overberg Test Range and has optical tracking capabilities that can contribute to SSA.

- Nigeria has partnered with international agencies to integrate satellite tracking into its defence communications network.

- Algeria and Egypt have invested in ground stations capable of receiving orbital data from partner nations and monitoring their own spacecraft.

These capabilities are often enhanced through partnerships. The African Union’s African Space Policy and Strategy (2016) identifies SSA as a priority, and some member states have tapped into international data-sharing agreements to access orbital information.

Partnerships and Data Sharing

SSA is inherently global—no single nation can monitor every object in orbit. African countries are engaging in multilateral arrangements to fill capability gaps:

- The United States Space Command shares orbital data with partner nations through its SSA Sharing Program.

- The European Space Agency (ESA) provides debris monitoring and conjunction warnings to operators, including those in Africa.

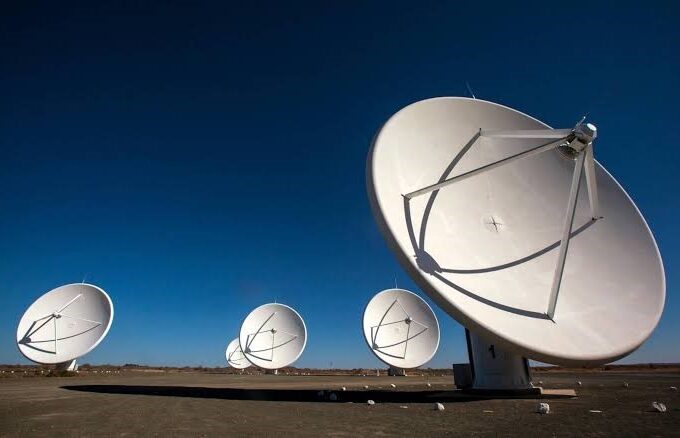

- The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project in South Africa, though primarily for radio astronomy, is exploring how its technology might contribute to space monitoring.

Such partnerships provide immediate benefits, but they also highlight the long-term need for African-owned infrastructure to ensure strategic independence.

Protecting Assets in Orbit

Once a threat is detected, operators can take several protective measures:

- Collision Avoidance Manoeuvres: Adjusting a satellite’s orbit to steer clear of debris.

- Signal Hardening: Using encryption and frequency-hopping to counter jamming or spoofing.

- Redundancy: Deploying multiple satellites with overlapping coverage so that the loss of one does not cripple operations.

- Cybersecurity Protocols: Protecting ground control systems through network segmentation, intrusion detection, and strict access controls.

African military space programmes are beginning to integrate such measures. Nigeria’s Defence Space Administration, for example, has incorporated cybersecurity into its satellite operations training.

The Cost Factor

SSA infrastructure is expensive. Radar arrays, tracking telescopes, and data processing centres require significant investment, as do the skilled engineers and operators to run them. For many African nations, the challenge is balancing these costs against other pressing defence and development priorities.

Regional cooperation offers a potential solution. An African Space Situational Awareness Network, pooling resources from multiple countries, could establish shared tracking sites in strategically dispersed locations—from North Africa’s deserts to Southern Africa’s high plateaus. This would improve orbital coverage while spreading costs and fostering interoperability.

The Military Imperative

The militarisation of space is accelerating. China, the United States, Russia, and India have all demonstrated ASAT capabilities, and the strategic value of space-based intelligence is higher than ever. For African militaries, the ability to safeguard satellites is not a luxury—it is a necessity for operational sovereignty.

Military satellites support:

- Counterterrorism: Providing geospatial intelligence on insurgent camps.

- Maritime Security: Tracking vessels involved in piracy or illegal fishing.

- Border Surveillance: Monitoring remote frontiers that are otherwise inaccessible.

- Disaster Response: Delivering rapid mapping of flood or earthquake zones.

Losing these capabilities in a crisis—whether to debris, cyberattack, or hostile action—could have severe national security consequences.

The African Space Agency (AfSA), headquartered in Egypt, is positioned to play a central role in developing continental SSA capacity. Its mandate includes promoting collaboration in space science and technology, which could extend to building a shared orbital monitoring framework.

Technological advances may also help bridge the capability gap. Commercial smallsat operators are developing low-cost tracking systems, and artificial intelligence is improving predictive modelling of orbital dynamics. African nations could adopt these solutions more quickly than traditional radar networks, leapfrogging some stages of infrastructure development.

Africa’s growing reliance on military satellites makes Space Situational Awareness an urgent strategic priority. While current capabilities are limited, a mix of international partnerships, regional cooperation, and targeted investment can help African nations protect their orbital assets.

In the same way that air defence protects sovereignty in the skies, SSA safeguards sovereignty in space. For African defence planners, the challenge is clear: without the means to see and understand the environment in which their satellites operate, they cannot fully secure the missions those satellites support.

The continent’s next frontier in defence is not just on land, at sea, or in the air—it is above, in the silent, contested, and increasingly vital realm of space.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace17

- Border Security15

- Civil Security6

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense24

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army9

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation7

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Policies1

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces2

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized6

- UNSC1

- Veterans7

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

THE DAWN OF VIGILANT SKIES: AFRICA’S EMERGING AIRBORNE EARLY WARNING CAPABILITIES

Africa’s airspace is undergoing a strategic transformation as a growing number of...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 15, 2026AIR & AEROSPACE – AIR DEFENCE SYSTEMS IN AFRICA: AN UNFINISHED BUSINESS

By December 2025, Africa’s air defence picture remains uneven, shaped by rising...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALODecember 24, 2025AFRICAN AIR FORCES RISE TO THE FOREFRONT IN COUNTERTERRORISM OPERATIONS

Across the vast and volatile regions of Africa, air forces once limited...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALONovember 21, 2025THE SPACE RACE: AFRICA’S EMERGING AEROSPACE PROGRAMMES

Africa’s skies are no longer just a backdrop to other powers’ ambitions...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 6, 2025