AIR & AEROSPACE – AIR DEFENCE SYSTEMS IN AFRICA: AN UNFINISHED BUSINESS

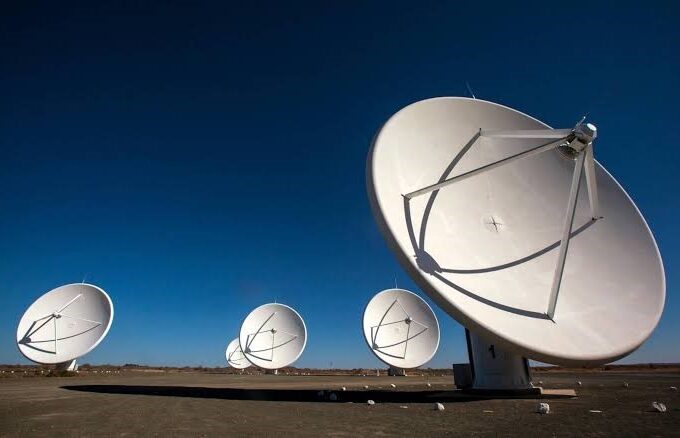

By December 2025, Africa’s air defence picture remains uneven, shaped by rising aerial threats and limited capacity to counter them. While a handful of states have invested in layered, modern systems, much of the continent still depends on fragmented or obsolete defences. The rapid spread of drones—used by both state and non-state actors—has exposed these gaps. From Sudan to the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin, armed groups now deploy unmanned systems for surveillance, strikes, and intimidation, exploiting airspace that is poorly monitored and lightly defended. Building credible air defence networks has become a pressing, yet incomplete, task.

Egypt fields the continent’s most developed air defence architecture. It maintains a dedicated Air Defence Forces branch equipped with long-range Russian S-300 systems complemented by U.S.-supplied Patriot batteries and locally upgraded components. Recent efforts have focused on countering low-altitude threats, including the integration of short-range systems on naval platforms to defend against drones and cruise missiles. Egypt’s strategy of diversifying suppliers has improved resilience and coverage around strategic sites. At the same time, analysts note the challenge of integrating systems from different origins into a seamless command-and-control network capable of responding to fast-evolving threats.

Related Articles: SKIES OF ALLIANCE: HOW JOINT AIR EXERCISES RESHAPED GLOBAL AEROSPACE SECURITY IN 2025

Algeria has pursued a more concentrated approach, relying heavily on Russian technology. The acquisition of S-400 systems in 2024 added depth to an existing network built around S-300 variants and Pantsir-S1 point-defence units. These assets are designed to protect Algeria’s vast territory and key installations while deterring regional adversaries. The emphasis on long- and medium-range interception reflects lessons drawn from recent conflicts elsewhere. However, reliance on a single supplier brings its own risks, particularly in maintenance, upgrades, and exposure to sanctions-related disruptions.

Morocco has leaned toward Western-oriented solutions, prioritizing air power and surveillance. The introduction of F-16V fighter jets strengthens its ability to contest airspace, while expanded radar coverage improves early warning. Short-range systems demonstrated during multinational exercises point to a growing focus on counter-drone defence, especially around sensitive sites. Yet Morocco’s posture remains centered on aircraft rather than a fully developed, ground-based air defence network, leaving gaps against saturation drone attacks or low-flying threats.

South Africa presents a different case. The country has strong technical foundations and indigenous systems such as the Umkhonto missile, designed for naval and potential land-based air defence. Ongoing development work points toward more advanced strike and interception capabilities. In practice, however, chronic underfunding has limited operational readiness. Ageing radars, grounded aircraft, and delayed procurement have reduced the effectiveness of existing defences. Ambitious plans to integrate autonomous systems and artificial intelligence remain largely conceptual.

Across much of sub-Saharan Africa, air defence capabilities are minimal. Many states rely almost exclusively on man-portable air-defence systems, which offer limited coverage and are poorly suited to countering small, low-cost drones. Nigeria’s experience illustrates the problem. As Boko Haram and ISWAP increasingly use UAVs for reconnaissance and attacks, Abuja has sought improved radar coverage and layered defences, but progress has been uneven. Ethiopia’s deployment of Pantsir-S1 systems provides localized protection, yet national-level coverage remains incomplete.

The spread of drones has transformed the threat environment faster than defences have adapted. In conflicts across Sudan, Mali, Burkina Faso, and Somalia, armed groups have used commercially available drones modified to carry explosives, bypassing traditional air defence assumptions. At the same time, state-operated systems such as the Bayraktar TB2 have reshaped conventional operations, raising the bar for detection and interception. Airbases, ports, energy facilities, and urban centers are now exposed to persistent, low-cost aerial threats.

External partners offer options but no simple solution. The United States emphasizes training and short-range systems through joint exercises. Russia continues to supply proven platforms such as the Pantsir family. China has expanded its footprint with comparatively affordable systems and surveillance technology. Yet procurement remains fragmented, training pipelines are thin, and supporting infrastructure radars, data links, command centers lags behind.

Without sustained investment and coordination, Africa’s airspace will remain vulnerable. Regional cooperation through African Union frameworks, shared early-warning mechanisms, and focused investment in counter-UAS technologies could narrow the gap. Until then, air defence across much of the continent remains unfinished business, increasingly tested in an era where control of the skies is no longer the preserve of advanced air forces alone.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace17

- Border Security15

- Civil Security6

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense24

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army9

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation7

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Policies1

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces2

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized6

- UNSC1

- Veterans7

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

THE DAWN OF VIGILANT SKIES: AFRICA’S EMERGING AIRBORNE EARLY WARNING CAPABILITIES

Africa’s airspace is undergoing a strategic transformation as a growing number of...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 15, 2026AFRICAN AIR FORCES RISE TO THE FOREFRONT IN COUNTERTERRORISM OPERATIONS

Across the vast and volatile regions of Africa, air forces once limited...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALONovember 21, 2025THE SPACE RACE: AFRICA’S EMERGING AEROSPACE PROGRAMMES

Africa’s skies are no longer just a backdrop to other powers’ ambitions...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 6, 2025MILITARY HELICOPTERS IN AFRICAN OPERATIONS

Military helicopters have become important assets in African operations, offering unmatched versatility...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOSeptember 23, 2025