DEFENCE DIPLOMACY AS A TOOL OF AFRICAN SOFT POWER

As global geopolitics grows more complex, African states are increasingly turning to defence diplomacy as a strategic instrument for advancing peace, civil security, and regional stability. Rather than relying on coercive military power, defence diplomacy emphasizes cooperation through joint exercises, intelligence sharing, capacity building, and sustained security dialogue. This approach reflects Africa’s long-standing preference for consensus-driven diplomacy and positions the continent as a constructive actor in international affairs while addressing internal and regional security challenges through partnership rather than force.

Defence diplomacy gained prominence after the Cold War, when militaries worldwide began shifting from purely combat-oriented roles to broader functions supporting foreign policy objectives. In Africa, this shift has taken on a distinctive character, blending military engagement with cultural, economic, and political outreach. Analysts often describe this as a calibrated mix of influence and deterrence that allows states to shape outcomes without escalation. South Africa, in particular, has embraced this model within the Southern African Development Community, promoting collective security arrangements that prioritize prevention, dialogue, and shared responsibility. This approach also reflects a broader effort to reclaim African agency in security affairs after decades of external dominance.

Related Articles: DEFENCE OFFSETS AND LOCAL MANUFACTURING: ARE AFRICANS BENEFITING?

Morocco offers another example of how defence diplomacy intersects with broader national strategy. Its expanding military cooperation across Africa is complemented by cultural and economic engagement, reinforcing its image as a stable and capable regional partner. The country’s co-hosting of the 2030 FIFA World Cup with Spain and Portugal serves not only as a diplomatic milestone but also as a signal of political confidence, infrastructure readiness, and international credibility. Nigeria, by contrast, illustrates a more security-driven adaptation of defence diplomacy. Faced with insurgency and transnational crime, it has combined cooperative military partnerships with strengthened defence capabilities, seeking to protect national interests while remaining engaged in regional and global security networks.

At its core, defence diplomacy in Africa is driven by the need to manage persistent threats such as terrorism, maritime insecurity, and border disputes. Multilateral initiatives, including shared training programs, joint defence projects, and intelligence coordination, are increasingly viewed as essential for building trust and preventing conflict. In regions where external actors compete for influence, defence diplomacy also enables African states to assert sovereignty while remaining open to collaboration on peacekeeping, humanitarian response, and disaster relief. South Africa’s framing of defence diplomacy as an indirect yet effective foreign policy tool captures this balance, using military assets to strengthen partnerships without provoking confrontation.

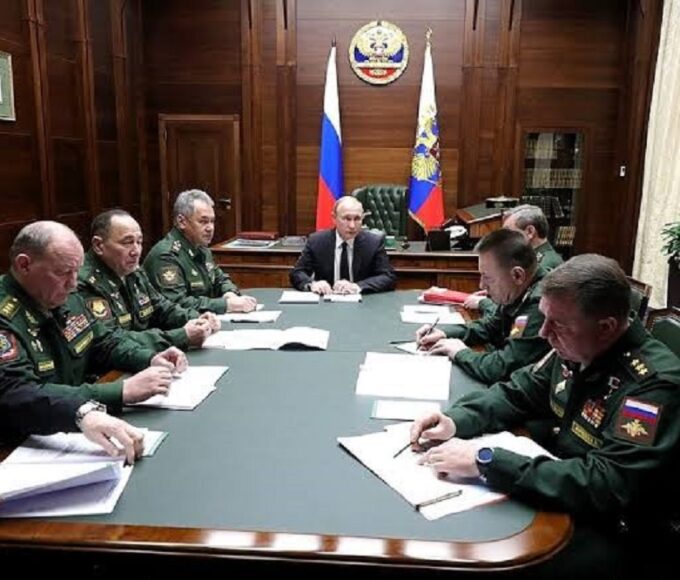

This strategy, however, unfolds amid intensifying competition among major powers. The United States integrates military cooperation with public diplomacy through training missions and joint exercises, viewing African militaries as partners in maintaining global security. China has expanded its influence through arms transfers, training programs, and military education, with African officers attending Chinese academies and later rising to senior command positions. Russia has pursued a more transactional approach, relying on private military actors in fragile states, offering short-term security support that often carries significant political and humanitarian risks.

These dynamics present challenges. Dependence on external partners can limit strategic autonomy, while gaps in transparency may undermine public trust. European states, including the United Kingdom, have sought to deepen military engagement with Africa through training and advisory roles, though funding constraints and shifting political priorities complicate these efforts. New technologies further reshape defence diplomacy. The growing focus on counter-drone systems and surveillance capabilities introduces advanced dependencies that may tie African states more closely to specific partners. In response, African leaders increasingly stress self-reliance and regional solidarity as the foundation of lasting security.

Despite these constraints, defence diplomacy has delivered tangible gains. It has helped reduce tensions, supported regional security pacts, and reinforced collective defence mechanisms, particularly in southern Africa. Its benefits also extend beyond security, aligning with development goals, environmental cooperation, and humanitarian initiatives. Historical examples of non-military engagement, such as Cuba’s long-standing medical cooperation in Africa, underscore how sustained support can generate trust and long-term goodwill that complements security objectives.

Looking ahead, defence diplomacy offers Africa a means to strengthen its soft power in a multipolar world. Its success will depend on prioritizing intra-African cooperation, maintaining strategic balance among external partners, and investing in indigenous capacity. If carefully managed, defence diplomacy can serve as a bridge between security and diplomacy, enabling African states not only to manage threats but also to shape their own role in an evolving international order.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace17

- Border Security15

- Civil Security6

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense24

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army9

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation7

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Policies1

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces2

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized6

- UNSC1

- Veterans7

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

BEST DEFENCE POLICY PAPERS ON AFRICA IN THE LAST DECADE

Between 2016 and 2026, defence policy thinking on Africa shifted in response...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 26, 2026BEST DEFENCE POLICY PAPERS ON AFRICA IN THE LAST DECADE

Between 2016 and 2026, defence policy thinking on Africa shifted in response...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 23, 2026THE ALGERIAN WAR OF INDEPENDENCE: TACTICAL LESSONS

The Algerian War of Independence (1954–1962) remains one of the most instructive...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 22, 2026DEFENCE MINISTERS’ MEETINGS: OUTCOMES THAT MATTER

As geopolitical pressures intensified in 2025, defence ministers’ meetings shifted from routine...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 21, 2026

Leave a comment