SHADOWS ACROSS BORDERS: AFRICA’S BATTLE AGAINST CROSS-BORDER BANDITRY AND EMERGING SECURITY STRATEGIES

Cross-border banditry has become one of West Africa’s most destabilising security challenges, blurring the line between organised crime and insurgency while displacing hundreds of thousands of civilians. Operating across poorly governed frontier zones, armed groups conduct village raids, cattle theft, kidnappings for ransom, and weapons trafficking. Their mobility often on motorcycles allows them to exploit the region’s vast and lightly policed borders, particularly across the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin.

Northwest Nigeria illustrates the scale of the crisis. Since the escalation of violence, more than 120 villages have been destroyed and over 247,000 people displaced, many seeking refuge in Niger’s Maradi region, where attacks have also intensified. What began as localized criminality has evolved into a transnational security threat, sustained by cross-border supply chains and weak state presence.

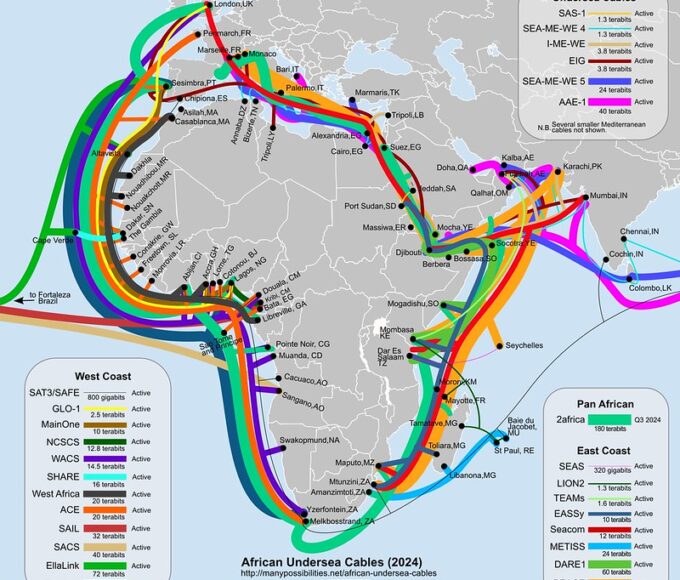

Related Articles: BENEATH THE SURFACE: AFRICA’S UNDERSEA CABLES AND RISING NATIONAL SECURITY RISKS

The drivers of banditry are deeply rooted. Porous borders, chronic poverty, competition over land and water, and the spread of illicit weapons have created a permissive environment. The contiguous zone spanning northwest Nigeria and southwest Niger has emerged as a major hotspot, underpinned by illegal gold mining and large-scale cattle rustling. In 2025 alone, violence in this corridor surged, with more than 2,200 fatalities recorded in the first half of the year exceeding the total toll of the previous year. The situation deteriorated further as criminal networks increasingly aligned with jihadist factions, including Lakurawa, which Nigeria formally designated a terrorist organisation.

The threat is no longer confined to traditional flashpoints. Along the borders of Benin, Niger, and Nigeria, armed groups linked to Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State Sahel Province (ISSP) have expanded southward. Their operations increasingly intersect with local bandit networks, creating hybrid threats that challenge conventional security responses. Attacks on military positions in northern Benin in early 2025, which killed dozens of soldiers, underscored the vulnerability of coastal states to Sahelian spillover.

State responses have struggled to keep pace. National military offensives, often conducted in isolation, have yielded limited results. Bandits exploit jurisdictional boundaries, launching attacks in one country and retreating across borders beyond the reach of pursuing forces. Political frictions have further undermined cooperation; diplomatic tensions following coups in the Sahel disrupted joint patrols between Nigeria and Niger for extended periods, weakening already fragile border security arrangements.

Recognising these limitations, regional actors are experimenting with new cooperative models. The Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), comprising forces from Nigeria, Niger, Chad, Cameroon, and Benin, has demonstrated the value of cross-border operations in the Lake Chad Basin. Although primarily focused on Boko Haram and Islamic State-linked insurgents, its structure offers a template for addressing banditry through shared command, intelligence, and operational coordination.

In the central Sahel, Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have taken a more sovereignty-driven approach through the Alliance of Sahel States (AES). In late 2025, the bloc launched a 5,000-strong Unified Joint Force to counter terrorism and organised crime across shared borders, replacing the now-defunct G5 Sahel framework. The initiative reflects a broader recalibration of regional security cooperation following the withdrawal of these states from ECOWAS.

Technology is also reshaping counter-banditry strategies. Unmanned aerial vehicles are increasingly deployed to monitor remote borderlands, while proposals in countries like Nigeria emphasise the use of satellite imagery, biometric systems, and artificial intelligence to track movement patterns. Intelligence fusion centres and real-time data sharing mechanisms are gradually gaining traction, enabling security agencies to anticipate raids rather than merely respond to them.

Despite these advances, significant obstacles remain. Funding constraints, uneven capacity among partner states, and lingering mistrust continue to undermine sustained collaboration. The growing convergence between bandit groups and jihadist organisations further complicates responses, raising the stakes for regional security.

As the crisis evolves toward 2026, it is increasingly clear that fragmented national efforts are inadequate. Hybrid approaches combining joint military frameworks, technology-driven surveillance, and community-based engagement offer the most credible path toward restoring state authority in Africa’s border regions and containing a threat that thrives on division and neglect.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace17

- Border Security15

- Civil Security6

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense24

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army9

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation7

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Policies1

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces2

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized6

- UNSC1

- Veterans7

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

BENEATH THE SURFACE: AFRICA’S UNDERSEA CABLES AND RISING NATIONAL SECURITY RISKS

Africa’s digital economy depends on infrastructure that few citizens ever see. Thousands...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 13, 2026GLOBAL SECURITY WATCH: IRAN–ISRAEL TENSIONS AND STRATEGIC SIGNALS FOR AFRICA

The brief but intense Iran–Israel confrontation of June 2025 marked a turning...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 7, 2026THE ROLE OF TRADITIONAL RULERS IN SECURITY DIPLOMACY

Africa treasures its traditional institutions Traditional rulers, kings, emirs, chiefs, and paramount...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALONovember 14, 2025ECOWAS MILITARY INTERVENTION IN NIGER: A TURNING POINT?

The coup d’état in Niger on July 26, 2023, marked a seismic...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 7, 2025

Leave a comment