BENEATH THE SURFACE: AFRICA’S UNDERSEA CABLES AND RISING NATIONAL SECURITY RISKS

Africa’s digital economy depends on infrastructure that few citizens ever see. Thousands of kilometers of submarine fiber-optic cables lie on the ocean floor, carrying more than 95 percent of the continent’s international data traffic. Financial markets, government communications, cloud services, and mobile networks all rely on these undersea links. As global geopolitical tensions increasingly extend into the maritime domain, however, these cables are no longer viewed as neutral commercial assets. They have become strategic infrastructure, and their vulnerability is now a matter of national security for African states.

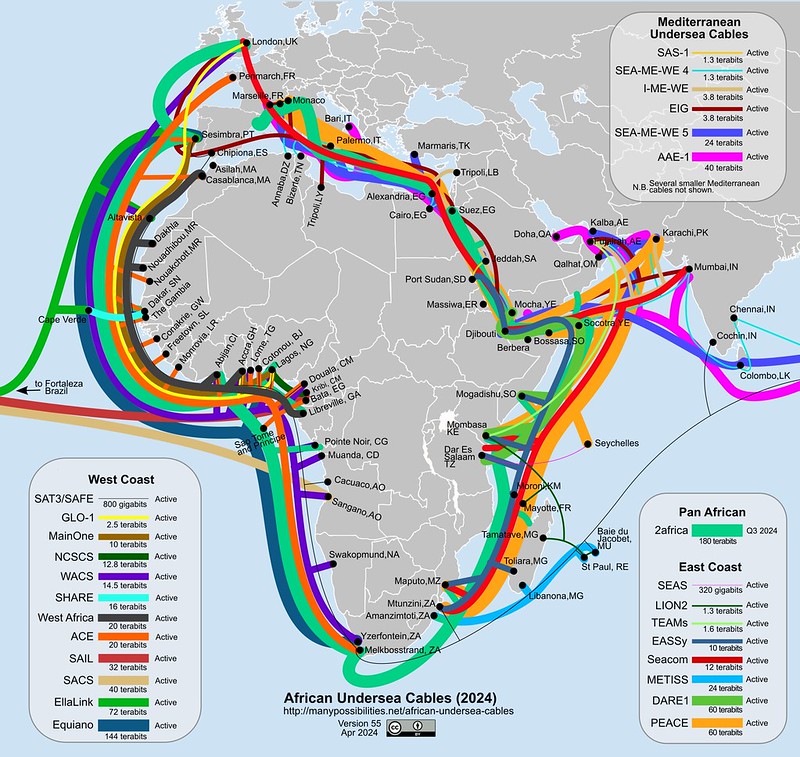

Over the past decade, Africa’s undersea cable network has expanded rapidly. Major systems such as the 37,000-kilometer 2Africa cable backed by a consortium that includes Meta, MTN, and China Mobile are designed to dramatically increase bandwidth and connect the continent more tightly to Europe, the Middle East, and Asia. While this expansion has lowered data costs and improved connectivity, it has also created structural risks. Cable routes are heavily concentrated along narrow maritime corridors, notably the Red Sea, the Mediterranean approaches, and the Gulf of Guinea. In these zones, multiple systems converge within limited seabed space, meaning a single incident can disrupt connectivity across several countries.

Related Articles: GLOBAL SECURITY WATCH: IRAN–ISRAEL TENSIONS AND STRATEGIC SIGNALS FOR AFRICA

That vulnerability became evident in 2024, when damage to cables in the Red Sea caused widespread internet outages across East Africa. Similar failures off the coast of Côte d’Ivoire in March of the same year knocked out major systems including WACS, MainOne, ACE, and SAT-3, cutting digital access across much of West Africa. These incidents demonstrated how localized disruptions can have continental consequences, affecting banking systems, air traffic management, and government services within hours.

The threats facing undersea cables are both accidental and deliberate. Globally, fishing activity and ship anchors remain the leading causes of cable damage, with dozens of breaks reported each year. Africa’s coastal waters add further risks from seismic activity and undersea landslides. Increasingly, however, security analysts are focused on intentional interference. Conflict zones have exposed cable routes to heightened danger, as seen in the Red Sea where Houthi attacks on commercial shipping raised the risk of collateral damage to nearby cables. Repair operations in such environments are slow, expensive, and often delayed by security constraints.

More troubling is the growing concern over deliberate sabotage as a tool of state competition. Reports of Russian vessels operating near European and African cable routes have reinforced fears that undersea infrastructure could be targeted as part of hybrid warfare strategies. China’s investments in deep-sea technology, including specialized cable-cutting capabilities, have further sharpened debate over the militarization of the seabed. While no African state has accused a foreign power of direct sabotage, the strategic implications are clear: cable disruption offers a low-visibility means of exerting pressure without crossing traditional thresholds of armed conflict.

These dynamics place Africa at the intersection of great-power rivalry. The United States has moved to restrict Chinese involvement in cable systems linked to its networks and has advanced legislation aimed at protecting subsea infrastructure. For African countries, many of whose cables are foreign-owned and financed, this competition raises difficult questions about sovereignty, data security, and long-term dependence. The cable routes that once mirrored colonial trade patterns are now central to digital connectivity, reinforcing concerns about external control over critical infrastructure.

African responses remain uneven. Some governments are prioritizing redundancy by supporting new routes such as the Medusa cable linking North Africa to Europe, while others are investing in data localization to reduce reliance on international transit. Naval forces in countries like South Africa and Nigeria have increased maritime patrols, but limited resources constrain continuous monitoring of vast exclusive economic zones. Satellite communications are often cited as a fallback option, yet high costs and latency make them unsuitable as full substitutes for fiber-optic networks.

International cooperation has become a key pillar of cable security. Western-backed initiatives promoting “trusted” digital infrastructure are expanding across Africa, while multilateral discussions increasingly frame undersea cables as critical infrastructure requiring collective protection.

Africa’s dependence on undersea cables is set to deepen as new projects connect the continent to Asia and South America. The strategic question is no longer whether these cables matter to national security, but whether African states can protect assets they neither fully own nor physically control.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace17

- Border Security15

- Civil Security6

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense24

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army9

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation7

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Policies1

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces2

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized6

- UNSC1

- Veterans7

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

SHADOWS ACROSS BORDERS: AFRICA’S BATTLE AGAINST CROSS-BORDER BANDITRY AND EMERGING SECURITY STRATEGIES

Cross-border banditry has become one of West Africa’s most destabilising security challenges,...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 16, 2026GLOBAL SECURITY WATCH: IRAN–ISRAEL TENSIONS AND STRATEGIC SIGNALS FOR AFRICA

The brief but intense Iran–Israel confrontation of June 2025 marked a turning...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOJanuary 7, 2026THE ROLE OF TRADITIONAL RULERS IN SECURITY DIPLOMACY

Africa treasures its traditional institutions Traditional rulers, kings, emirs, chiefs, and paramount...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALONovember 14, 2025ECOWAS MILITARY INTERVENTION IN NIGER: A TURNING POINT?

The coup d’état in Niger on July 26, 2023, marked a seismic...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 7, 2025

Leave a comment