SYSTEMS & TECHNOLOGY – 3D PRINTING AND AFRICA’S DEFENCE INDUSTRY REVOLUTION

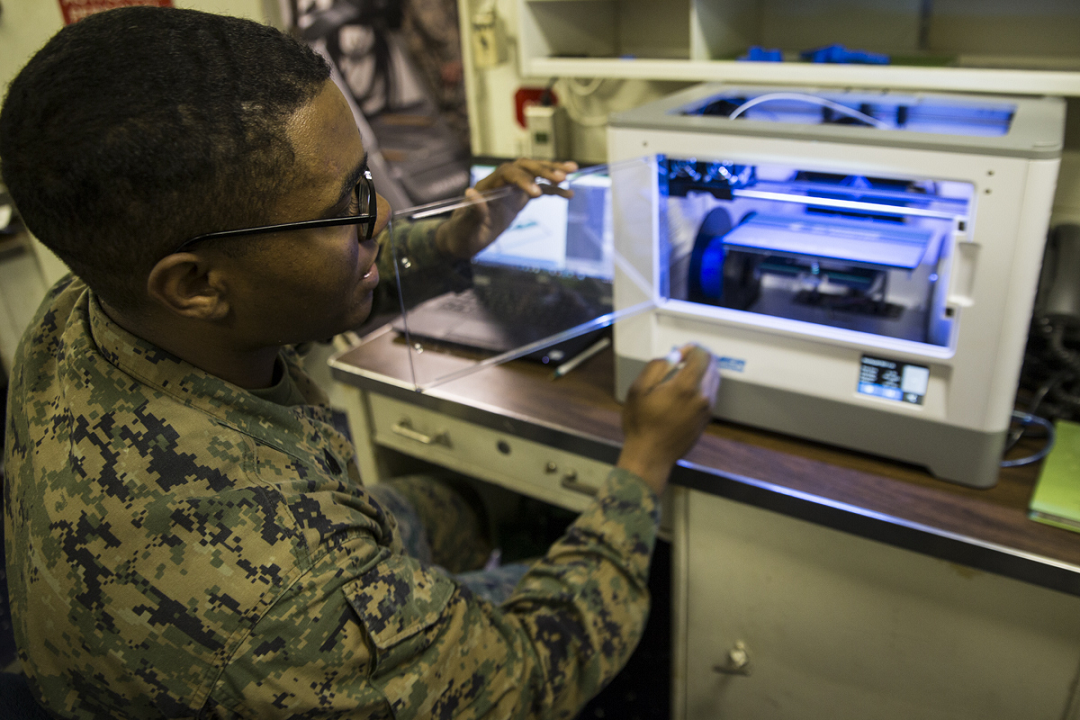

In modern warfare, where speed and adaptability can determine survival, 3D printing or additive manufacturing has emerged as a quiet revolution in Africa’s defence sector. Across the continent, militaries face vast terrains, fragile supply chains, and persistent security challenges, from insurgencies to border disputes. Traditional defence manufacturing, with its reliance on imports and complex logistics, often leaves African forces at a disadvantage.

3D printing changes the game. By layering metals, polymers, or composites to create complex parts on demand, the technology bypasses bottlenecks and delivers solutions directly to the battlefield. Whether in South Africa’s advanced facilities or forward-operating bases in the Sahel, additive manufacturing is enabling rapid prototyping, cost savings, and localized production ushering in a new era of strategic autonomy for African defence.

Related Article: THE NEXT FRONTIER IN TECH INNOVATION

Globally, the military adoption of 3D printing began in the early 2010s with the U.S. Department of Defence using it for drone swarms and spare parts. Africa’s embrace, however, is rooted in necessity. Defence budgets across the continent are projected to hit $50 billion by 2025, spurred by threats in the Horn of Africa and West Africa. For governments, additive manufacturing is more than a cost-saving measure it’s a pathway to independence from traditional Western suppliers. This aligns with the African Union’s Agenda 2063, which emphasizes technology-driven sovereignty. Countries like South Africa are already capitalizing on local resources such as titanium reserves to manufacture high-strength defence components. Instead of merely importing arms, African nations are beginning to innovate and contribute to global defence ecosystems.

South Africa leads this transformation. Its state-owned defence giant, Denel, and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) are pioneering world-class projects. Notably, the Project Aero swift initiative produced the world’s largest metal 3D printer, capable of fabricating parts up to two meters long using titanium powder. Practical results are already visible. A boat tail for Denel’s Marlin missile was reimagined as a single lightweight printed piece, cutting production time and reducing weight. The Ahrlac light attack aircraft now includes 3D-printed throttle grips and fuel strainers, manufactured with less waste and greater efficiency.

Beyond high-tech labs, 3D printing is proving its worth in real-world African operations. During Operation Barkhane in Mali, French troops used portable printers at their Gao base to create spare parts within hours whether an ignition button for a vehicle, protective casings for optics, or custom gaskets. In regions where sandstorms and long supply lines wreak havoc on logistics, this ability to “print and deploy” offers a decisive edge.

African militaries are following suit. Nigeria’s researchers are exploring 3D-printed drone parts and prosthetics for injured soldiers. Kenya has tested 3D-printed rifle suppressors and vehicle mounts in collaboration with local universities. Even informal networks are experimenting: West African blacksmiths have reportedly combined traditional craftsmanship with low-cost printers to create hybrid firearm attachments.

The advantages of this shift are profound. Defence procurement in Africa often comes with heavy mark-ups and months-long delays; 3D printing reduces costs by up to 90% for prototypes and compresses production timelines from months to days. Customization allows for terrain-specific solutions, whether it’s drones designed for Saharan heat or lighter armour for urban patrols. It also localizes supply chains. By printing with regional materials, countries reduce dependence on foreign suppliers and mitigate risks from sanctions a reality for states like Algeria or Zimbabwe.

Yet the path forward is not without obstacles. High-end printers, especially those capable of producing with advanced metals, remain expensive, leaving smaller militaries at a disadvantage. Training is another hurdle: only a fraction of African engineers are skilled in additive manufacturing, highlighting the urgent need for education and vocational programs.

Despite these hurdles, the potential is undeniable. Future visions include AI-assisted design, battlefield robotics, and mobile factories capable of printing drones or vehicles on demand. Regional cooperation, driven by bodies like the African Defence Industries Council, could foster a $5 billion additive manufacturing market by 2030. In a continent where climate change, cyber threats, and hybrid warfare are reshaping security challenges, 3D printing offers not just resilience but deterrence. It enables African nations to move from being perpetual consumers of foreign defence technology to becoming creators and innovators in their own right.

3D printing symbolizes Africa’s leap into strategic self-reliance. It transforms vulnerabilities fragile supply chains, dependence on imports into strengths by democratizing advanced manufacturing. The challenge for policymakers now is to ensure equitable access, build skills, and establish ethical frameworks so that this technology strengthens peace rather than fuels conflict. Layer by layer, Africa’s defence industry is being reborn crafting a future where the continent shapes its own security destiny.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace15

- Border Security14

- Civil Security3

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis4

- Cyber Security4

- Defense15

- Diplomacy17

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry6

- Land & Army7

- Leadership & Training3

- Military Aviation2

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- Naval & Maritime8

- Resources1

- Security12

- Special Forces1

- Systems And Technology8

- Tech6

- Uncategorized3

- UNSC1

- Veterans6

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

THE PUSH FOR MADE-IN-AFRICA AMMUNITION AND SMALL ARMS

For decades, Africa’s security has rested on foreign supply lines. More than...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALONovember 4, 2025AFRICA’S BLUE ECONOMY: UNLOCKING A WAVE OF SUSTAINABLE GROWTH

Africa’s blue economy represents one of the continent’s most promising frontiers for...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 3, 2025Sudan’s Mining Revival Begins with Russia, Putting African Resource Control in Focus

Sudan is betting on rocks—and maps—to rebuild its economy. The country has...

Byadmag_adminMay 31, 2025AFRICA’S CYBERSECURITY LANDSCAPE: FOCUS ON TANZANIA

Africa’s cybersecurity landscape is rapidly evolving, driven by the increasing adoption of...

Byadmag_adminMay 31, 2025