BORDER SECURITY AND MILITARISED WILDLIFE PROTECTION: AN EMERGING NEXUS

The Convergence of Conservation and Security

In an era where transnational threats blur the lines between environmental conservation and national security, militarised wildlife protection has emerged as a critical strategy. This approach involves deploying military forces, paramilitary units, and advanced surveillance technologies to safeguard endangered species, particularly in border regions where poaching and trafficking intersect with broader security concerns.

From Africa’s vast savannahs to Asia’s dense forests, countries are increasingly linking conservation efforts with border security to combat organised crime syndicates that exploit porous frontiers. Wildlife trafficking, valued at billions annually, not only decimates biodiversity but also funds insurgencies and terrorism, prompting governments to treat it as a national security imperative. This fusion aims to protect ecosystems while enhancing territorial integrity, but it raises profound questions about ethics, effectiveness, and community impacts.

READ ALSO: Militarised Wildlife Protection: Linking Border Security with Conservation

ROOTS OF MILITARISED CONSERVATION

The roots of militarised conservation often trace back to the escalation of poaching crises, where armed syndicates use military-grade weapons to target high-value species like elephants and rhinos. In response, nations have repurposed defence assets for anti-poaching operations, recognising that wildlife crimes frequently involve cross-border networks tied to smuggling, money laundering, and even militant groups. For instance, profits from ivory and rhino horn trades have been linked to funding groups like al-Shabaab, though some claims have been debunked. This securitisation of conservation is amplified in conflict zones, where instability allows poachers to operate with impunity, turning protected areas into battlegrounds that demand a militarised counter-response.

ADVANTAGES OF MILITARISED APPROACHES

Proponents argue that integrating military tactics into wildlife protection yields tangible benefits, such as deterring sophisticated poachers and fostering international cooperation. Enhanced patrols, drone surveillance, and joint operations across borders can reduce illegal activities while bolstering national security frameworks. In trans frontier conservation areas, this approach promotes diplomatic ties, as shared intelligence and resources help address mutual threats like rebel incursions disguised as poaching. Moreover, it provides rangers with better training and equipment, potentially saving lives in high-risk environments where over 1,000 rangers have been killed globally in the past decade.

CHALLENGES AND ETHICAL CONCERNS

However, critics highlight significant challenges, including human rights abuses and the alienation of local communities. Militarised strategies often prioritise force over engagement, leading to “shoot-to-kill” policies that result in civilian casualties and erode trust. Indigenous groups, reliant on these lands for livelihoods, face displacement, violence, and exclusion, perpetuating colonial legacies of control. Such tactics may also overlook root causes like poverty and corruption, diverting resources from sustainable alternatives like community-based conservation, which could yield longer-term success without the ethical pitfalls.

SOUTH AFRICA’S MILITARISED MODEL

South Africa exemplifies this militarised paradigm, particularly in Kruger National Park, where the South African National Parks (SAN Parks) collaborates with the military and private firms to combat rhino poaching. Rangers, led by retired army personnel, employ drones, canine units, and armed patrols along the Mozambique border, blending conservation with border security to counter syndicates. While this has reduced poaching incidents, historical abuses such as using wildlife nets to capture refugees in the 1980s underscore the risks of conflating human and wildlife threats. Marine areas also see militarised enforcement, with navy involvement in fishing restrictions.

KENYA’S INTEGRATED APPROACH

In Kenya, the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) integrates conservation with border policing in northern regions, training rangers in military tactics to address poaching linked to insurgent funding. British Army support has enhanced anti-poaching units, but reports of corruption in wildlife enforcement systems highlight internal challenges. This approach has protected species like elephants, yet it has sparked debates over excessive force and the need for judicial reforms to complement militarisation.

BOTSWANA’S AGGRESSIVE STANCE

Botswana stands out for its aggressive stance, with the Botswana Defence Force (BDF) assuming anti-poaching duties since the 1980s, authorising “shoot-to-stop” measures against armed intruders in national parks. Along the Chobe River border, this intersects with territorial disputes, where wildlife protection justifies military presence amid tensions with Namibia over resources. While effective in reducing cross-border crimes, incidents of civilian deaths have drawn international criticism, emphasising the tension between security gains and human costs.

GLOBAL PERSPECTIVES AND FUTURE CHALLENGES

Beyond Africa, countries like Nepal and India have adopted similar models, with military-trained units patrolling tiger reserves and borders to curb trafficking. In Nepal, WWF-backed programs have faced allegations of abuses against indigenous communities, mirroring global concerns.

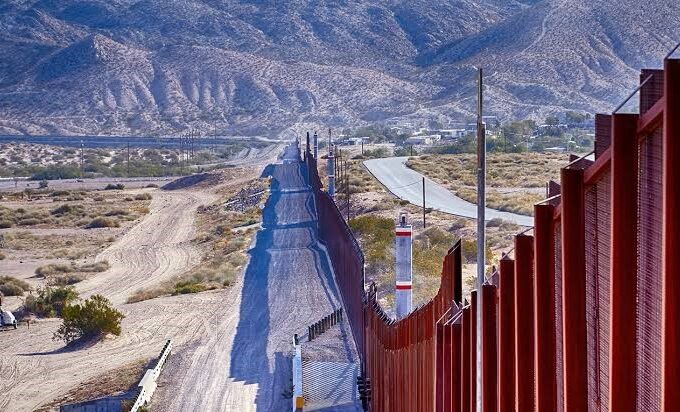

Meanwhile, in the United States, border security fences along the Mexico frontier fragment wildlife habitats, obstructing migration and illustrating how security measures can inadvertently harm conservation. As climate change exacerbates resource pressures, balancing militarised protection with inclusive strategies will be essential for sustainable outcomes worldwide.

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALO

King Richard Igimoh, Group Editor African Leadership Organisation is an award-winning journalist, editor, and publisher with over two decades of expertise in political, defence, and international affairs reporting. As Group Editor of the African Leadership Organisation—publishers of African Leadership Magazine, African Defence & Security Magazine, and Africa Projects Magazine—he delivers incisive coverage that amplifies Africa’s voice in global security, policy, and leadership discourse. He provides frontline editorial coverage of high-profile international events, including the ALM Persons of the Year, the African Summit, and the African Business and Leadership Awards (ABLA) in London, as well as the International Forum for African and Caribbean Leadership (IFAL) in New York City during the United Nations General Assembly.

Recent Posts

Categories

- Air & Aerospace16

- Border Security15

- Civil Security4

- Civil Wars4

- Crisis5

- Cyber Security8

- Defense19

- Diplomacy19

- Entrepreneurship1

- Events5

- Global Security Watch6

- Industry8

- Land & Army8

- Leadership & Training5

- Military Aviation5

- Military History27

- Military Speeches1

- More1

- Naval & Maritime9

- Resources2

- Security12

- Special Forces1

- Systems And Technology9

- Tech6

- Uncategorized3

- UNSC1

- Veterans6

- Women in Defence9

Related Articles

THE CASE FOR CONTINENTAL BORDER SECURITY STANDARDS

Africa’s borders remain both an opportunity and a liability. They enable trade,...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALODecember 27, 2025BORDER SECURITY – LESSONS FROM ECOWAS BORDER MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES

Since its founding in 1975, the Economic Community of West African States...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALONovember 21, 2025COMMUNITY INTELLIGENCE AT BORDERS: SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

Border security increasingly relies on community intelligence the collection and use of...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOOctober 6, 2025REFUGEE MOVEMENTS AND BORDER FORCE DILEMMAS

In today’s world of conflict, climate change, and widening economic divides, refugee...

ByKing Richard Igimoh, Group Editor ALOSeptember 24, 2025